Write Parameterized Tests In Jest

Table Of Contents

Unit tests are crucial - they help to confirm that the individual parts of applications work as intended.

On the one hand, without them you are never sure that everything works correctly, whether after refactoring or adding a new feature.

On the other hand, writing these tests takes a lot of time, especially if the code is duplicated to test different edge cases.

Skipping tests is not an option, therefore we need to look for a way to speed up the whole process.

Fortunately, Jest provides us with the ability to create Parameterized Tests that are designed exactly for this purpose.

Tests Duplication

In this section we will write some unit tests for a simple function that adds two values to see where the problem lies.

Create a function add(x, y):

const add = (x, y) => x + y;To verify that the function works as intended, we select random pairs of numbers and use them is tests:

describe("add function", () => {

it("should return proper result when passed arguments are: 0, 0", () => {

expect(add(0, 0)).toEqual(0);

});

it("should return proper result when passed arguments are: -1, -2", () => {

expect(add(-1, -2)).toEqual(-3);

});

it("should return proper result when passed arguments are: 1, 2", () => {

expect(add(1, 2)).toEqual(3);

});

it("should return proper result when passed arguments are: 99999, 99999", () => {

expect(add(99999, 99999)).toEqual(199998);

});

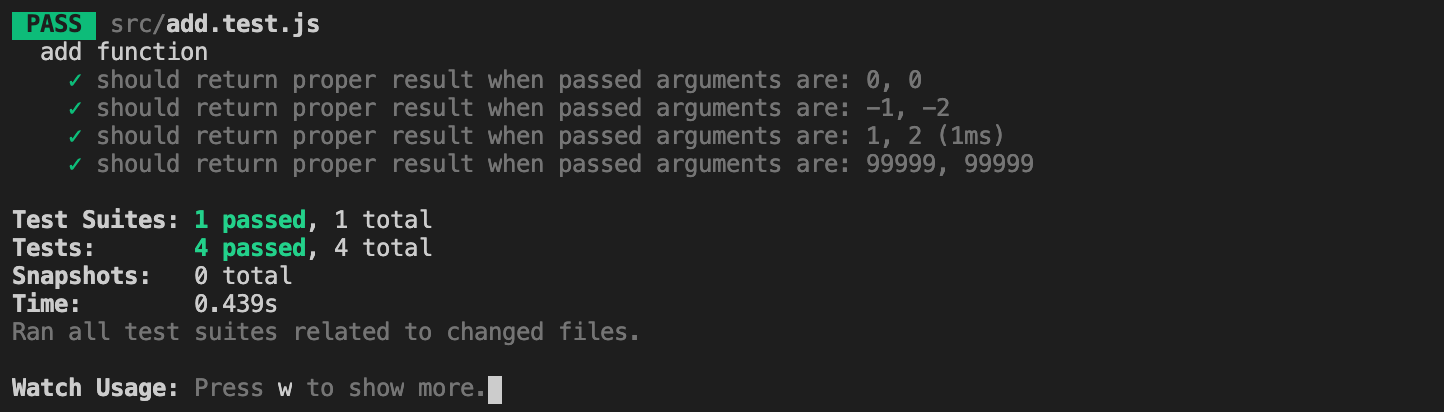

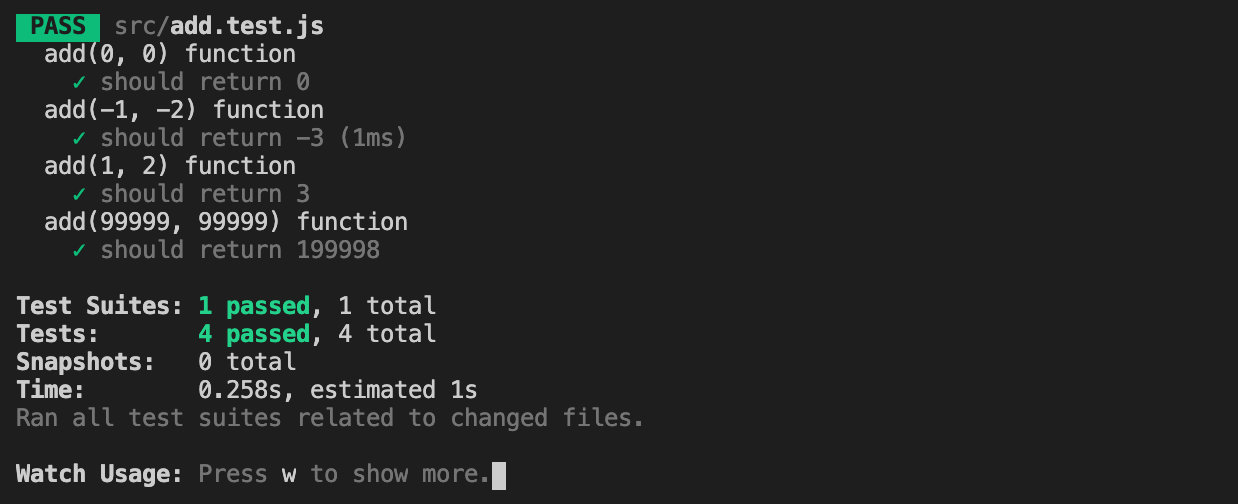

});Run the tests to see if they pass:

Great, we just tested our add(x, y) function and can move on to the next feature... but hey, haven't you noticed that we unnecessarily copied a lot of code?

The only things that change between tests are the arguments and the result.

It would be nice if you could declare them all in one place and just execute the assertion by iterating over it.

Parameterized Tests - Array Syntax

This is exactly what Jest allows us to do with the Parameterized Tests:

describe("add function", () => {

it.each([

[0, 0, 0],

[-1, -2, -3],

[1, 2, 3],

[99999, 99999, 199998],

])(

`should return proper result when passed arguments are: %i, %i`,

(x, y, result) => {

expect(add(x, y)).toEqual(result);

}

);

});Not sure what's going on here? Let me explain.

We use the built-in each function, which accepts a table (multidimensional array) as an argument:

[

[0, 0, 0],

[-1, -2, -3],

[1, 2, 3],

[99999, 99999, 199998],

]The table contains rows, each of which is passed to the test function (the order of the arguments is preserved):

// Syntax

(x, y, result) => {

expect(add(x, y)).toEqual(result);

}

// 1-st Iteration

(0, 0, 0) => {

expect(add(0, 0)).toEqual(0);

}

// 2-nd Iteration

(-1, -2, -3) => {

expect(add(-1, -2)).toEqual(-3);

}

// 3-d Iteration

(1, 2, 3) => {

expect(add(1, 2)).toEqual(3);

}

// 4-th Iteration

(99999, 99999, 199998) => {

expect(add(99999, 99999)).toEqual(199998);

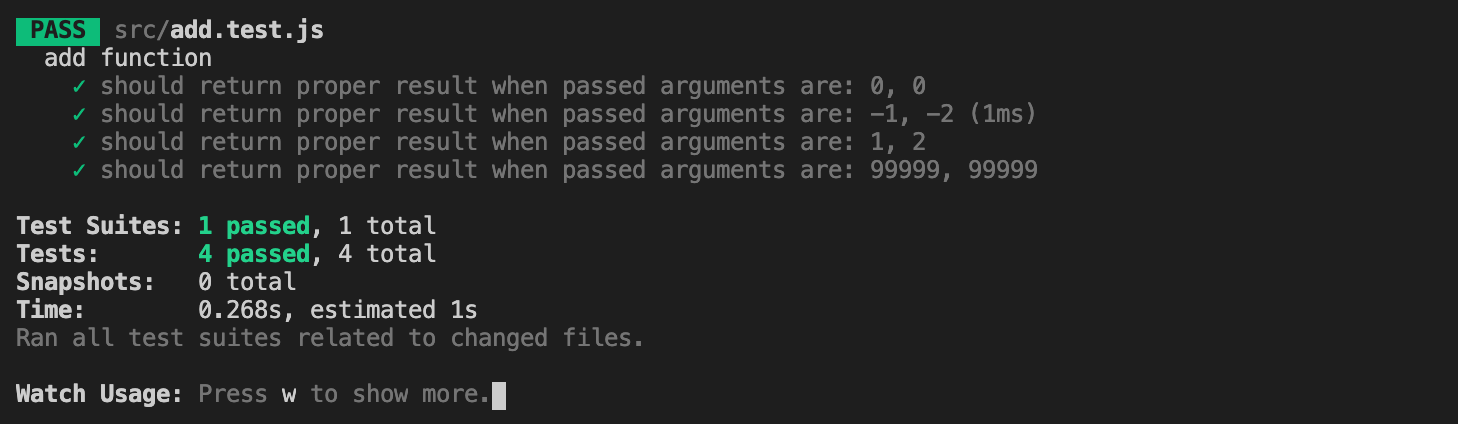

}Run the tests to verify that nothing is broken after the little refactoring:

Works fine!

You may also have noticed that we used %i in the test title.

This is used to positionally inject integer parameters with printf formatting.

If we remove it, the test title would not contain the arguments and it would be hard to understand what values are actually being tested:

describe("add function", () => {

// ...

'should return proper result when passed arguments are: ...',

// ...

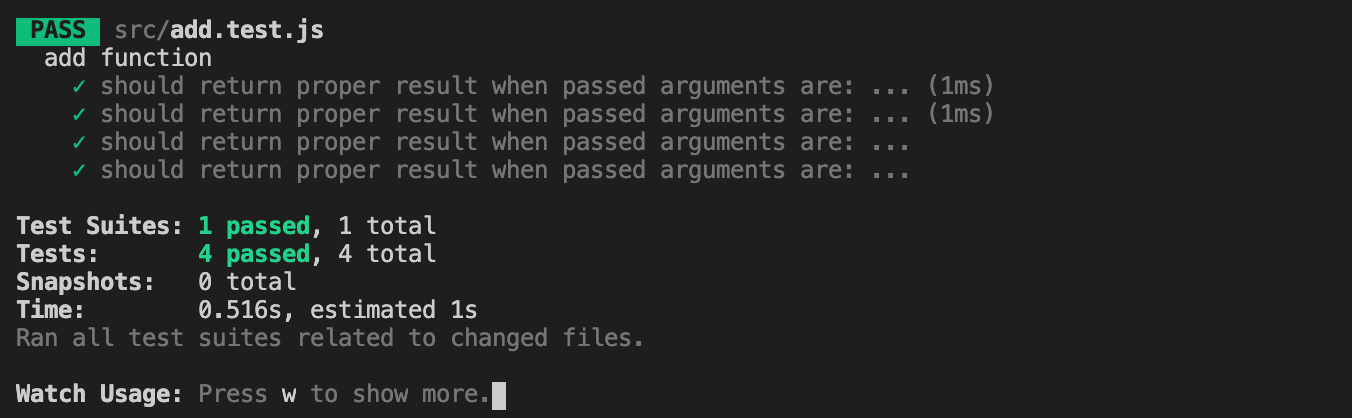

});Run tests with the title changed:

Therefore, it is always better to explicitly define which values are tested, unless we are talking about complex objects (but even in this case we can inject properties of this object).

See the full list of available injecting parameters and their formatting here.

Parameterized Tests - Tagged Template Literal Syntax

In the previous section, we defined the table argument as a multidimensional array, and that's perfectly fine.

But there's another way to define it - using Tagged Template Literal Syntax:

describe("add function", () => {

it.each`

x | y | result

${0} | ${0} | ${0}

${-1} | ${-2} | ${-3}

${1} | ${2} | ${3}

${99999} | ${99999} | ${199998}

`(

`should return proper result when passed arguments are: $x, $y`,

({ x, y, result }) => {

expect(add(x, y)).toEqual(result);

}

);

});It may look a bit more complicated, but believe me, it's not.

We pass a Tagged Template Literal with the following structure:

- The first row contains variable name column headings

- Subsequent rows contain data passed as Template Literal Expressions using ${value} syntax

In the test title, we can then access the data with the syntax $x, $y or $result and display an index of the current row with $#.

Within the test, we access the data by destructuring the first argument.

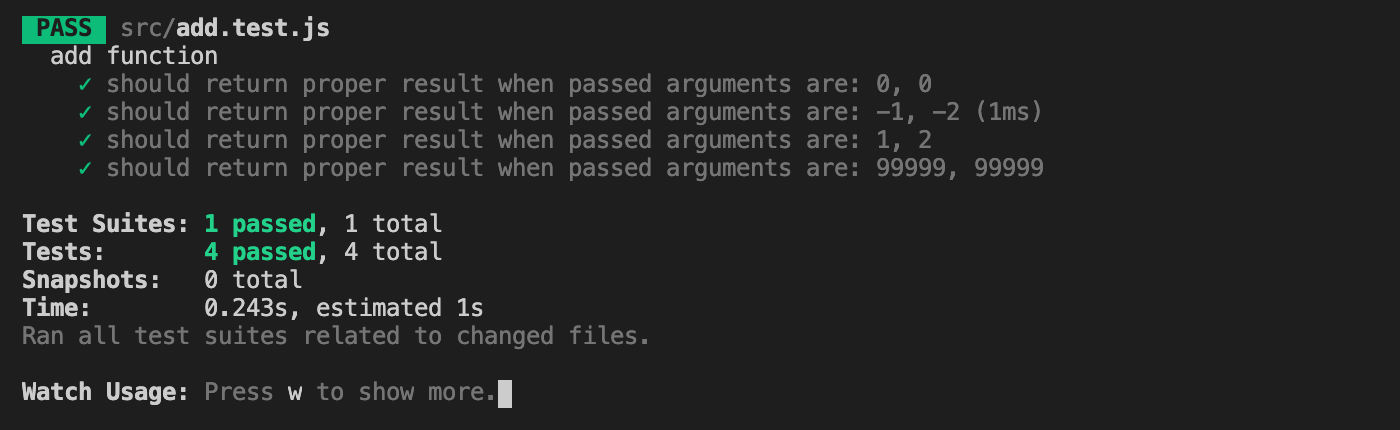

Finally, run the tests:

Still works well.

Parameterized Tests - Test Suits

In the previous sections, we learned how to use it.each to duplicate the same test with different data.

But tests can be grouped together in Test Suits.

Think of a Test Suit as of a container that groups related tests and helps in running them and reporting the results.

In our previous examples, we created a suit by using the describe method, which is actually provided by Jest.

It depends on your testing strategy how you split the tests into suits, because it is possible to have one suit per function, module, plugin, etc.

In some cases it is necessary to duplicate suits with different data.

We may the same .each pattern for Test Suits as we did for individual tests:

describe.each([

[0, 0, 0],

[-1, -2, -3],

[1, 2, 3],

[99999, 99999, 199998],

])(`add(%i, %i) function`, (x, y, result) => {

it(`should return ${result}`, () => {

expect(add(x, y)).toEqual(result);

});

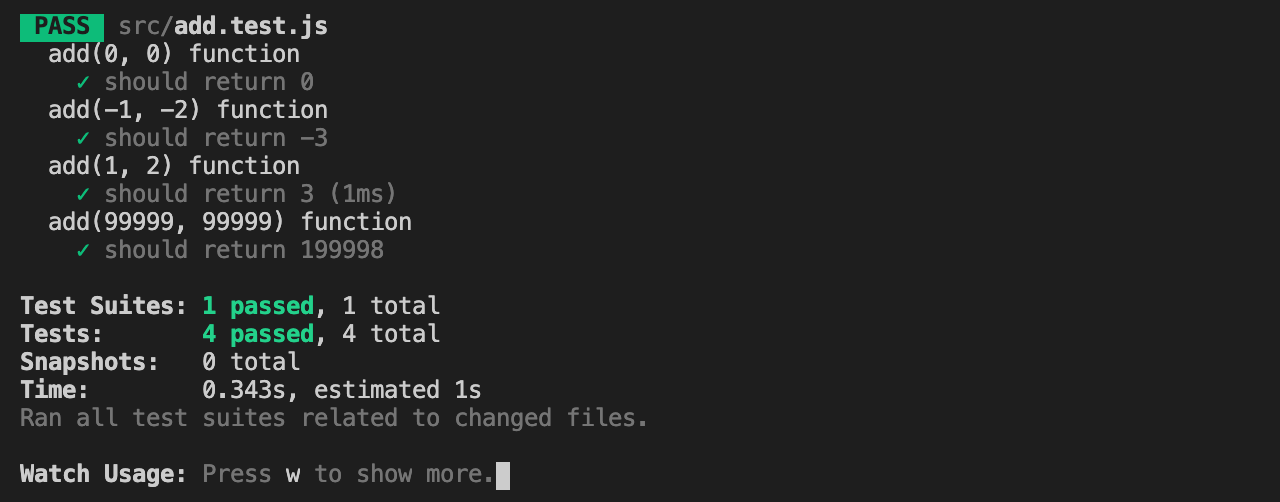

});Run the tests (Note that the report format has changed):

We can also use the Tagged Template Literal Syntax here:

describe.each`

x | y | result

${0} | ${0} | ${0}

${-1} | ${-2} | ${-3}

${1} | ${2} | ${3}

${99999} | ${99999} | ${199998}

`(`add($x, $y) function`, ({ x, y, result }) => {

it(`should return ${result}`, () => {

expect(add(x, y)).toEqual(result);

});

});Run the tests:

NPM Package: jest-each

If you were familiar with the topic before reading this article, you may know that there is an npm package called jest-each that provides basically the same functionality that we implemented today.

The package is still very popular with more than 13M weekly downloads (as of Sep 19th 2021).

But what's the point of installing and using it when Jest provides the ability to write Parameterized tests our-of-the-box?

The reason is simple - support for .each syntax was only added to Jest in version 23 and above.

Read the official information about it here.

If you use a smaller version, it is necessary to use the package.

Interesting fact: Jest uses the jest-each package under the hood.

Summary

In this article, we learned a simple way to reduce unit test boilerplate using Parameterized Tests in Jest.

There is no need to copy the tests changing only the input arguments - use either describe.each or jest.each to make the tests cleaner, shorter and more readable.