Git Stash Like A Pro

Table Of Contents

The developers work is often interrupted by requests to implement more important features or even to fix some critical bugs.

This situation leads to stopping the development and switching to another task, but what if you didn't manage to complete the current work and you are not ready to commit the changes?

You don't want to discard the changes and start over the next day, right?

Fortunately, Git provides a command to easily handle such situations.

Git Stash Command

The git stash command works like a clipboard - it temporarily saves the current state of a working directory and undoes it, so you can start coding new features from scratch.

You can get back to stashed changes and re-apply them at any time.

This is handy when you need to quickly switch context and work on something else without losing unfinished work.

Remember that stash is local to your repository - it will not be transferred to the server after pushing changes.

For example, I'm working on a secret feature on a feature/1 branch when I get a request to fix a bug noticed by a tester in production (in other words, on the main branch), but I'm only halfway done with my secret feature, so that's what I usually do:

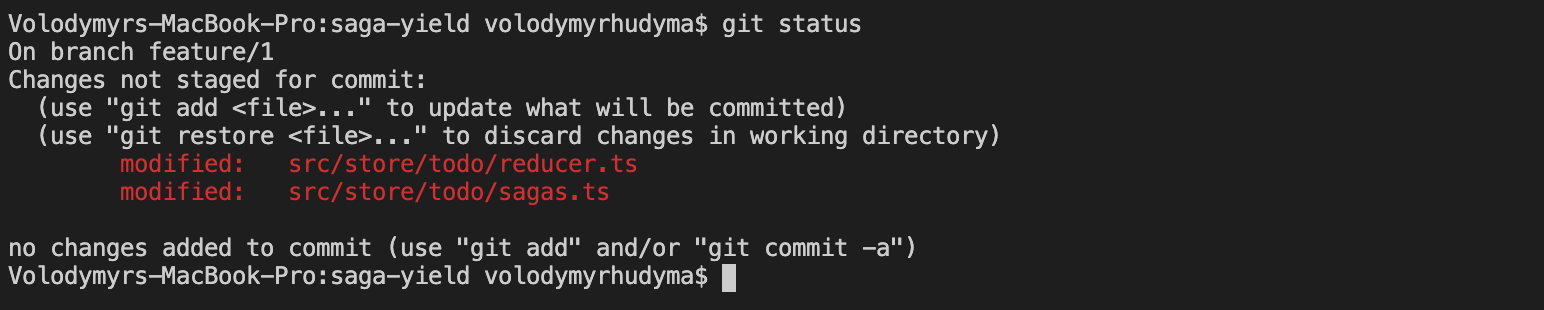

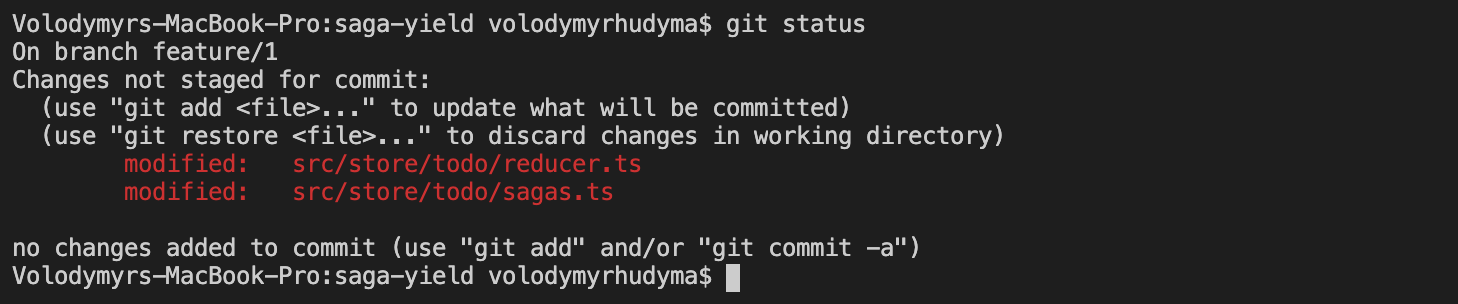

- Check how many changes have been made with a git status command:

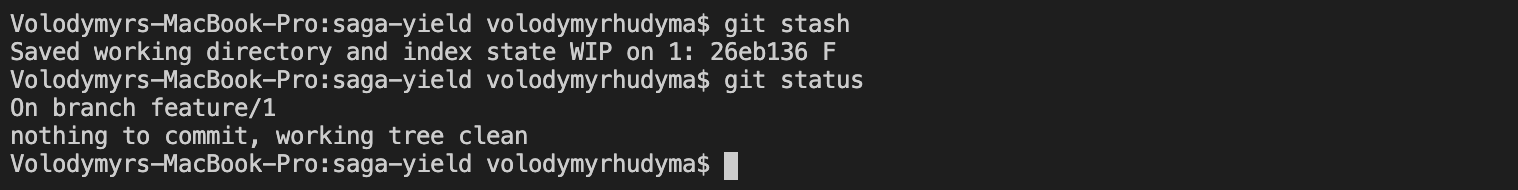

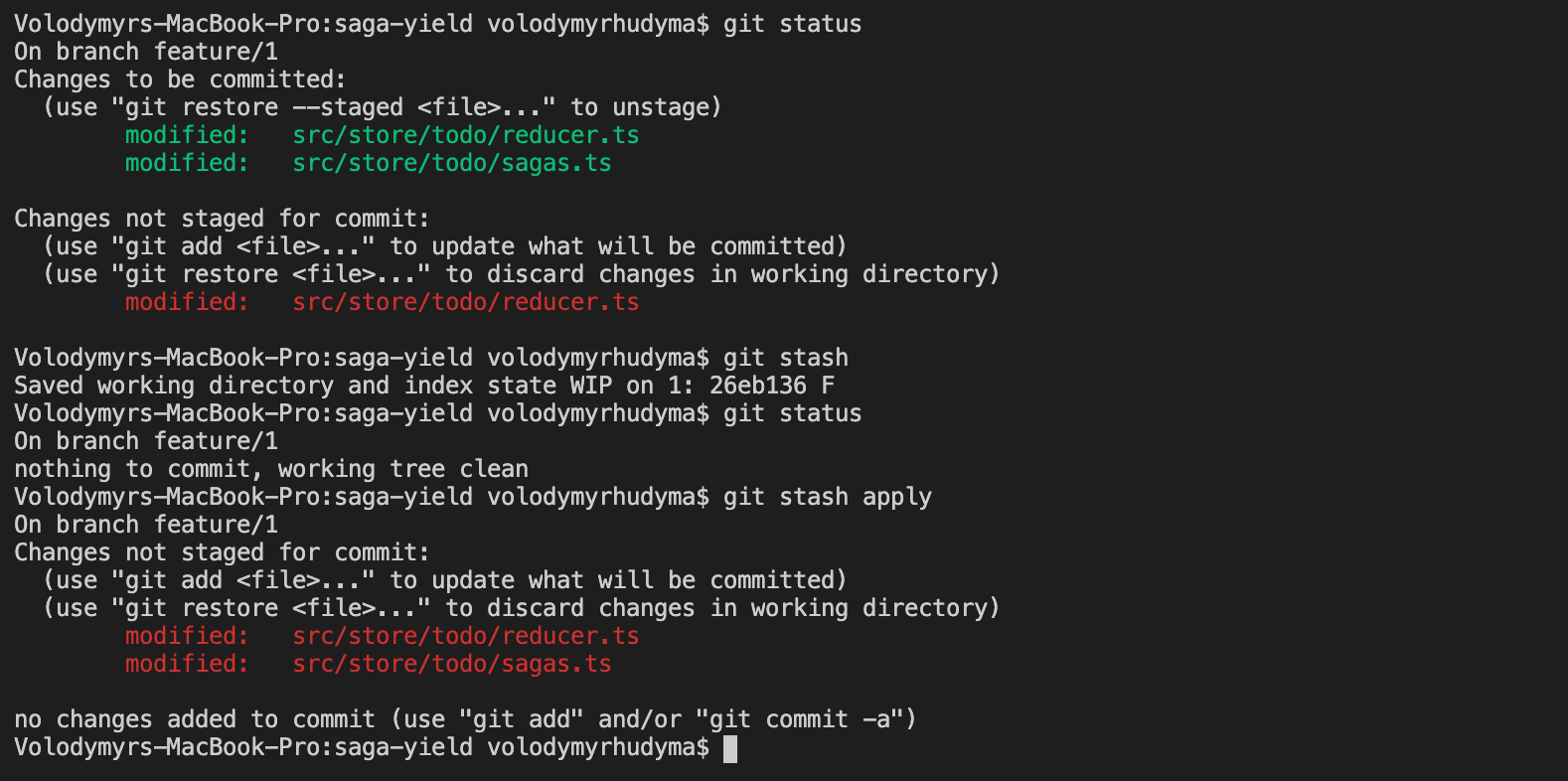

- Stash the changes with a git stash command:

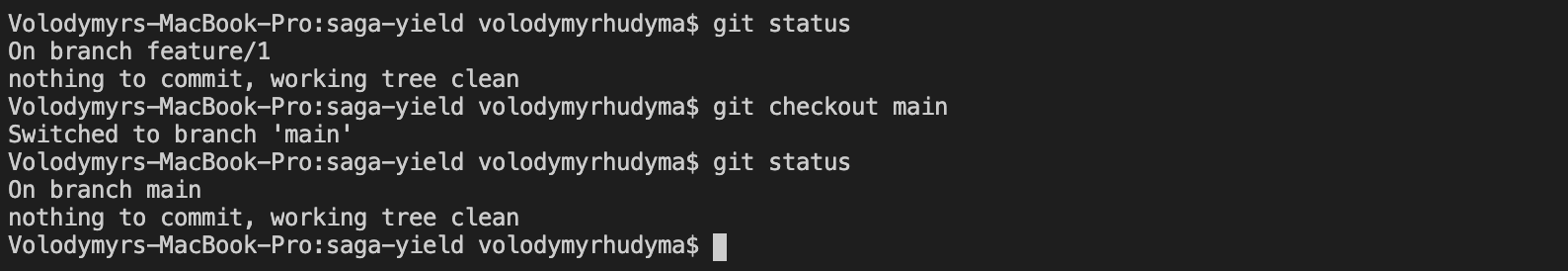

- Switch to the main branch with the git checkout main command and work on a bug fix:

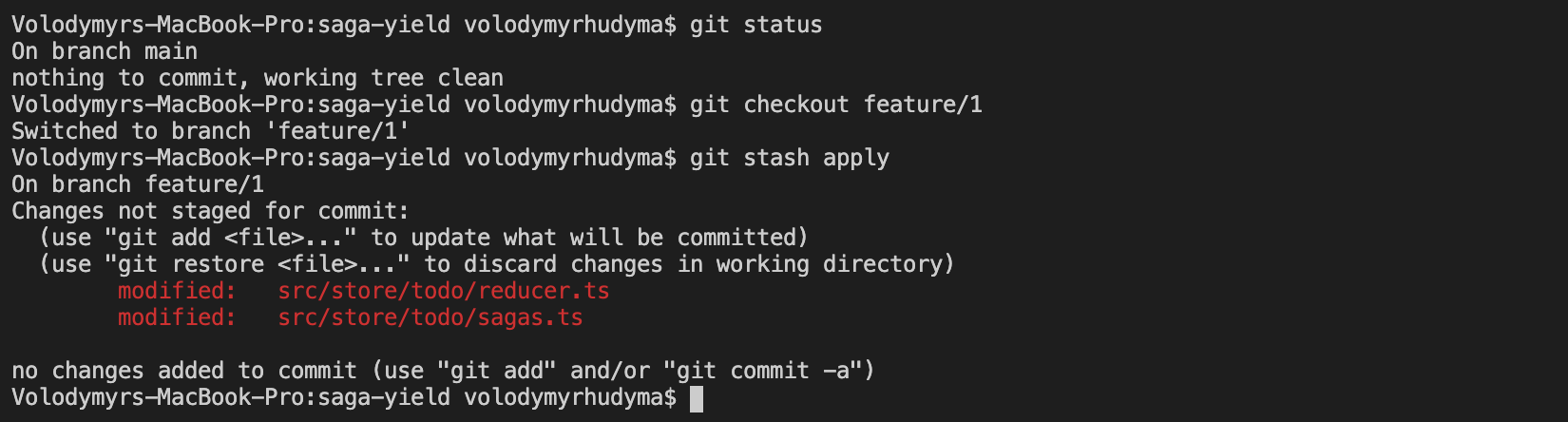

- Switch back to the feature/1 branch after the bug has been fixed, and re-apply the stashed changes with a git stash apply command:

Staged And Unstaged Changes In Git

Before you learn whether git stash works with both staged and unstaged changes, you should know what staged and unstaged changes are and how they differ.

Unstaged Changes

Unstaged changes are changes that exist in the working directory but haven't yet been added to the Git version history:

Git tells us that changes are unstaged with the following message: Changes not staged for commit.

Staged Changes

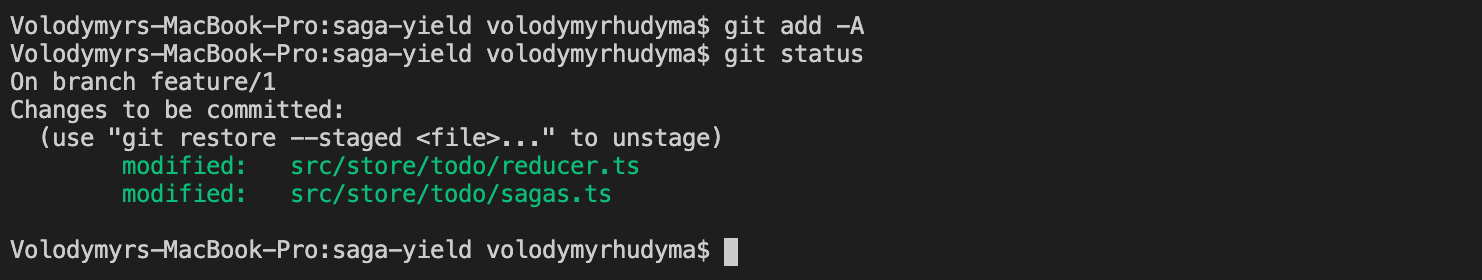

Staged changes are changes that should be committed the next time the git commit command is executed.

To move a change from unstaged to staged state, run the git add command.

Staged changes are usually marked with a green color:

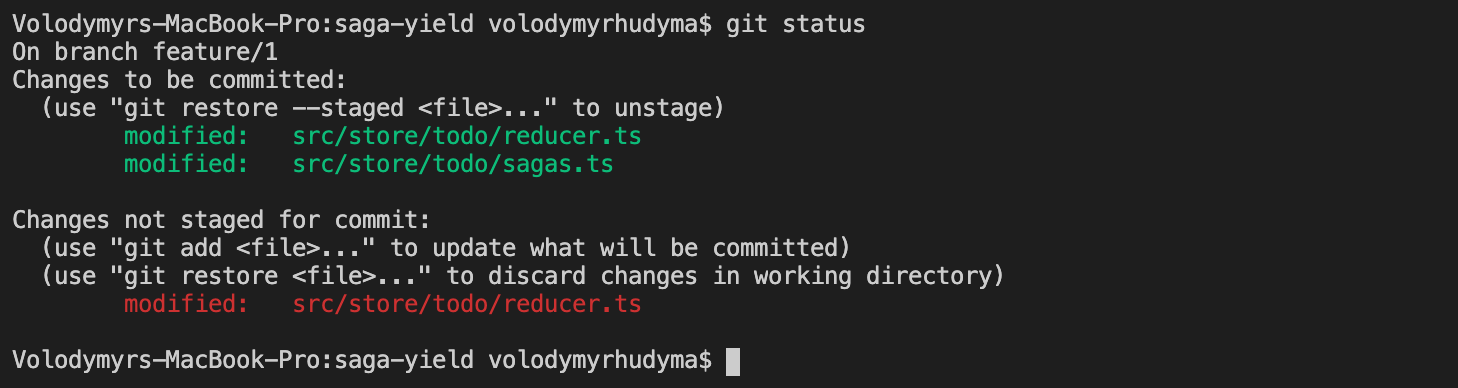

Staged And Unstaged Changes In The Same File

It is also possible to have both staged and unstaged changes in the same file:

Stashing Staged And Unstaged Changes

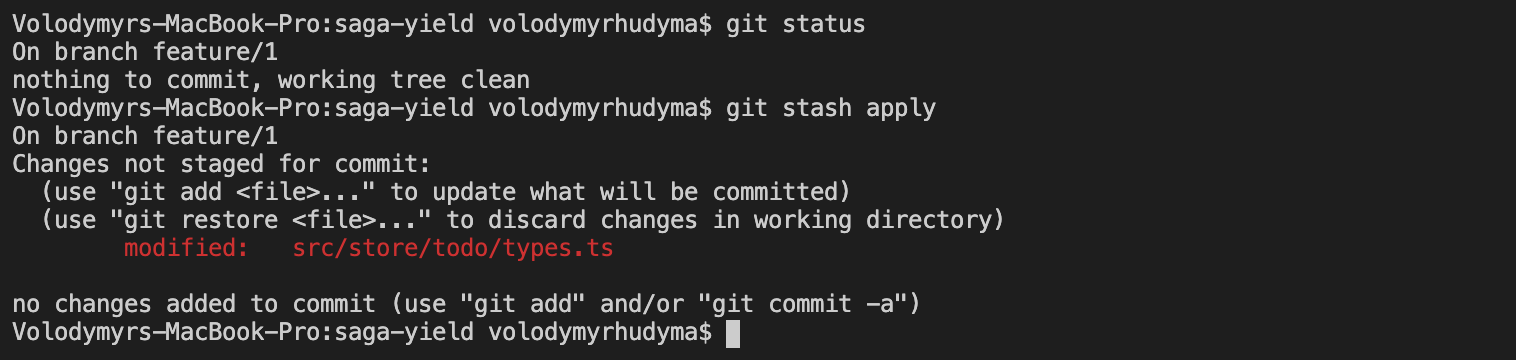

Now that we've learned what staged and unstaged changes are, we can answer the question - git stash command saves both staged and unstaged changes, but after re-applying them, all changes become unstaged:

Tracked And Untracked Files In Git

Now that we know that git stash is capable of working with both staged and unstaged changes, we need to know how it works with untracked and tracked files.

But before we answer that question, let's learn what untracked and tracked files are in Git.

Untracked Files

By default, when you create a new file in your working directory, it will show as untracked because it is not in the Git version system.

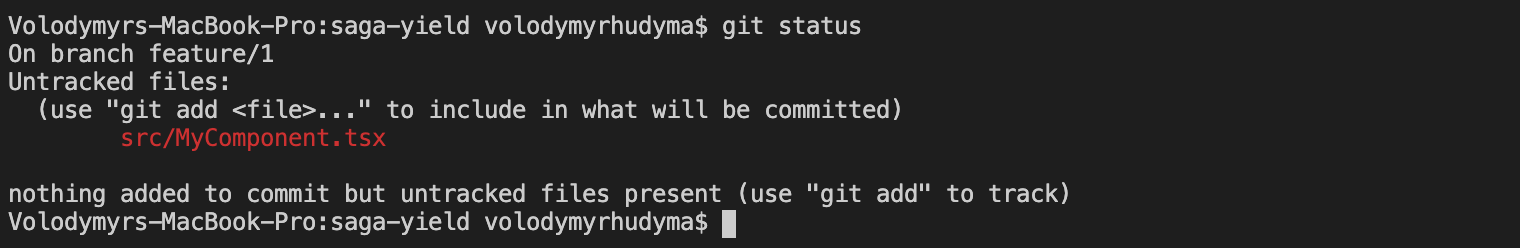

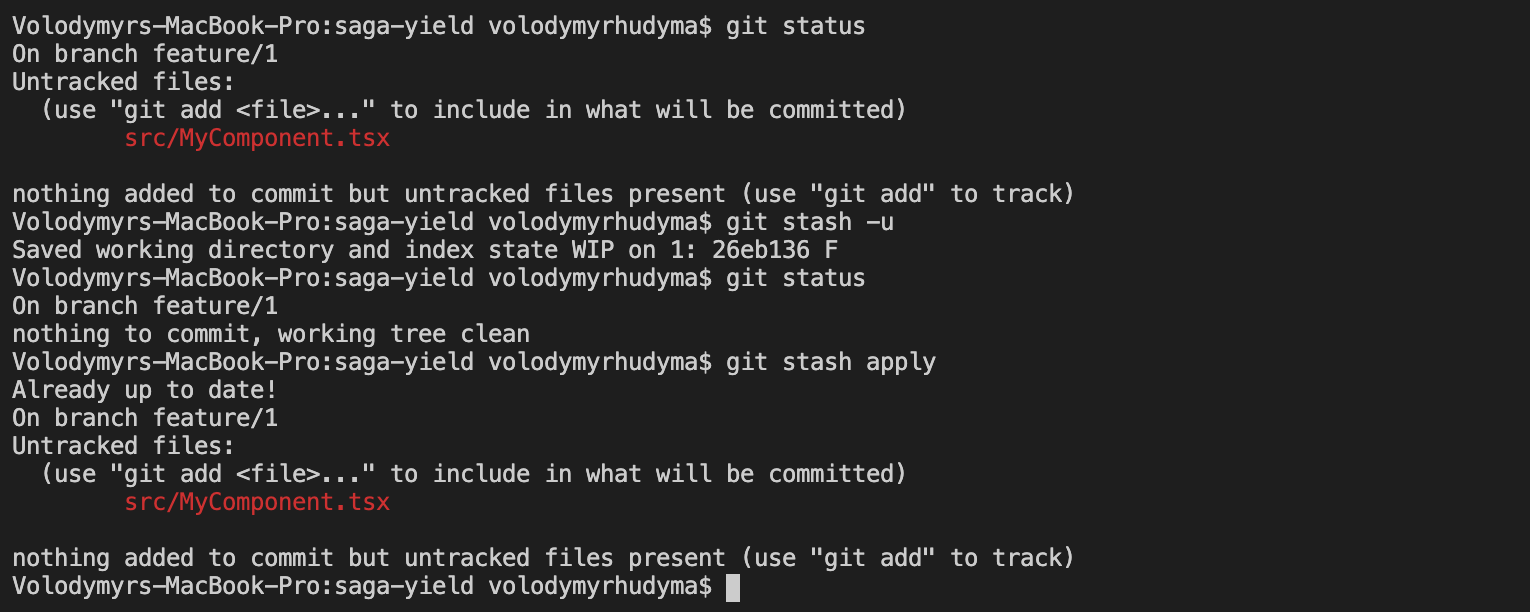

I created a new MyComponent.tsx component and executed the git status command:

Git tells us that the file is untracked with the following message: Untracked files.

Tracked Files

Tracked files are files that should be committed the next time the git commit command is executed.

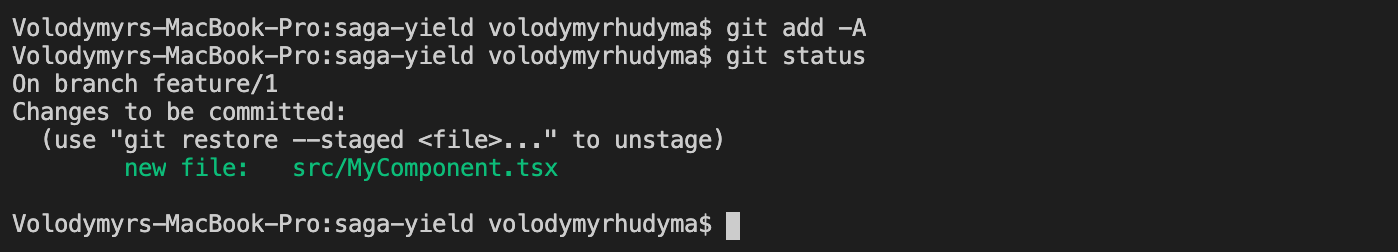

To move a file from the untracked to the tracked state, run the git add command.

Tracked files are usually marked with a green color:

Stashing Tracked And Untracked Files

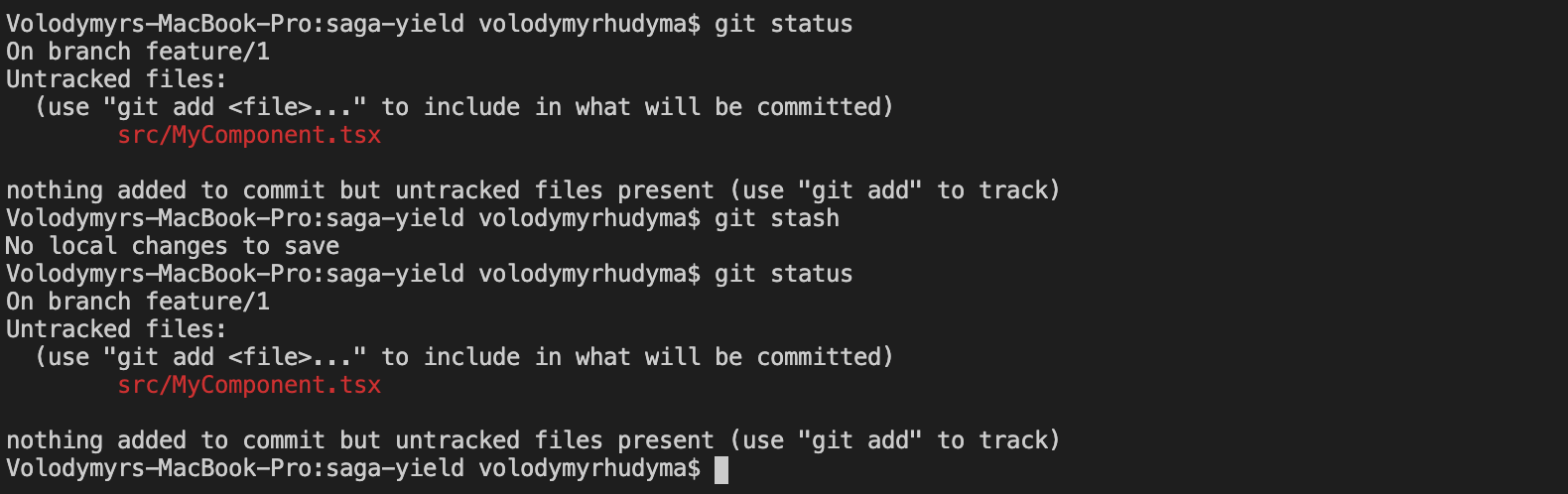

The git stash command does not store untracked files by default:

When we tried to stash an untracked file, Git responded with a message: No local changes to save.

This is because untracked files are not stored in Git.

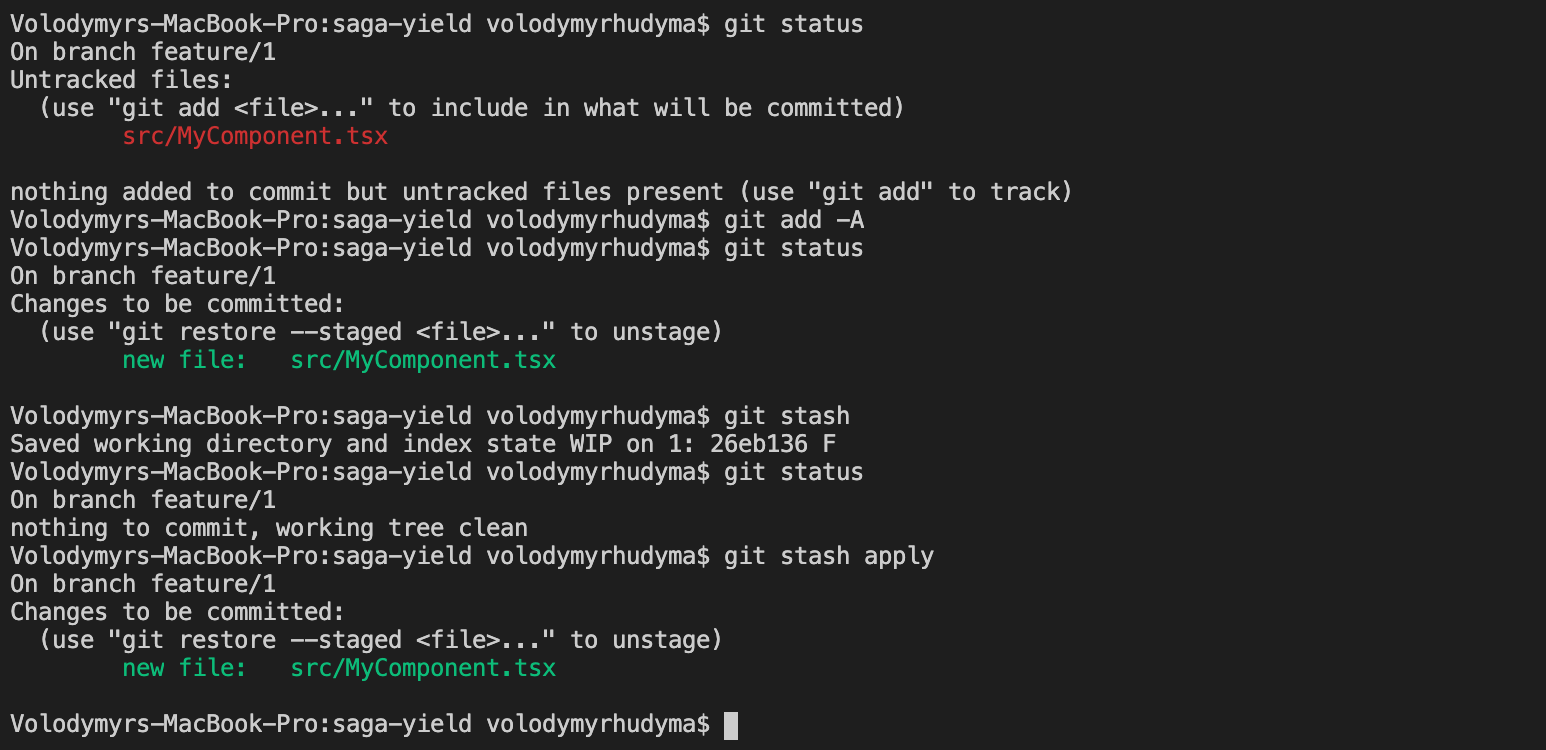

If the file is added to tracked with the git add command, it can be stashed and re-applied later:

However, there is a magic flag that enables stashing untracked files - (-u, or --include-untracked):

Stashing Ignored Files

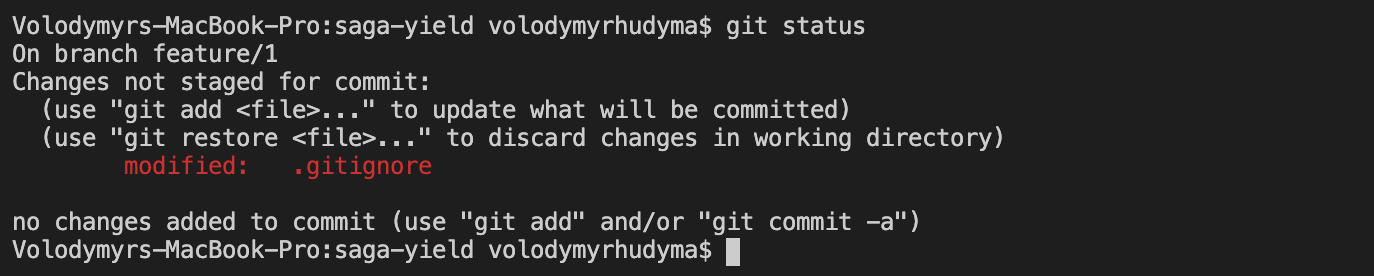

Another good question is whether git stash works with ignored files (an ignored file is a file that is tracked in a special file called .gitignore).

Obviously it doesn't by default, but we can get it working by using a magic flag - (-a or -all).

Let's add the newly added MyComponent.tsx to the .gitignore:

// ..

MyComponent.tsxAnd verify that it is indeed ignored (the git status command shows that we only changed the .gitignore file, but it does not show MyComponent.tsx as an untracked file):

Try to stash ignored file with the git stash -a command, and see that it has been re-applied after running git stash apply, even though it is ignored by Git.

Apply Stashed Changes

Stashed changes can be applied using one of the following commands:

git stash apply (or git stash apply stash@{<index>} if you want to apply a specific stash).

Or

git stash pop (or git stash apply pop@{<index>} if you want to pop a specific stash).

Both do the same thing, but there is one important difference between them.

The first command (git stash apply) applies changes and does nothing afterwards, while the second (git stash pop) removes the changes from the stash list after they have been applied:

List Stashed Changes

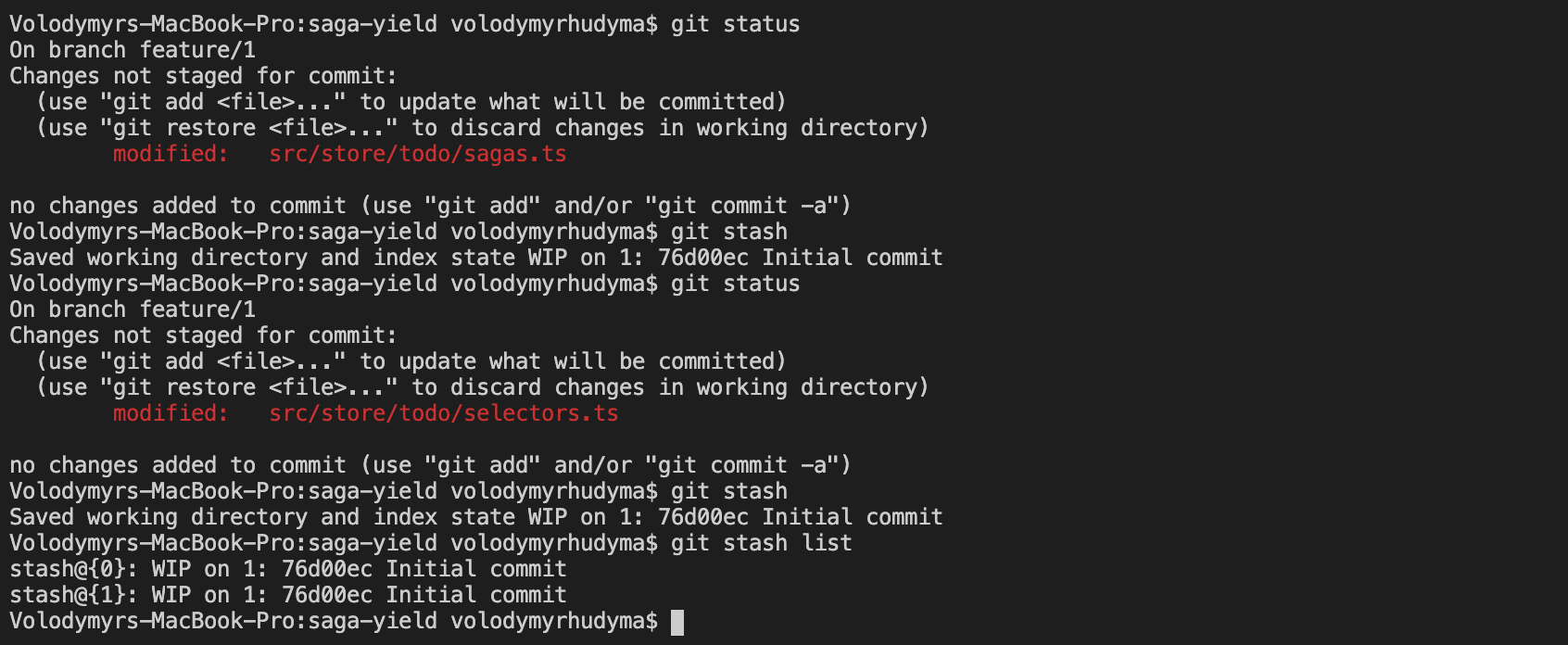

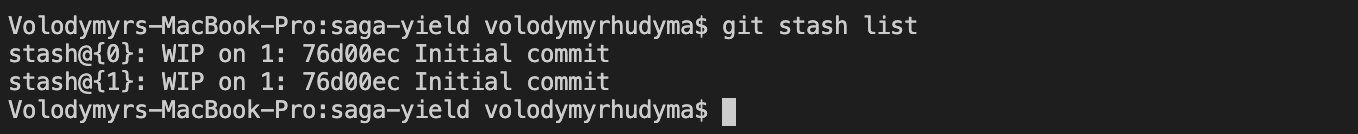

You are not limited to a single stash, you can run git stash command a few times and create multiple stashes:

To view all stashes, run the following command:

git stash list

Note that each stash is marked with WIP (Work In Progress) and a commit from which the stash was created:

Looking at the stash list above, it's hard to guess what changes are included in each stash, so it's a good practice to provide a description for each stash.

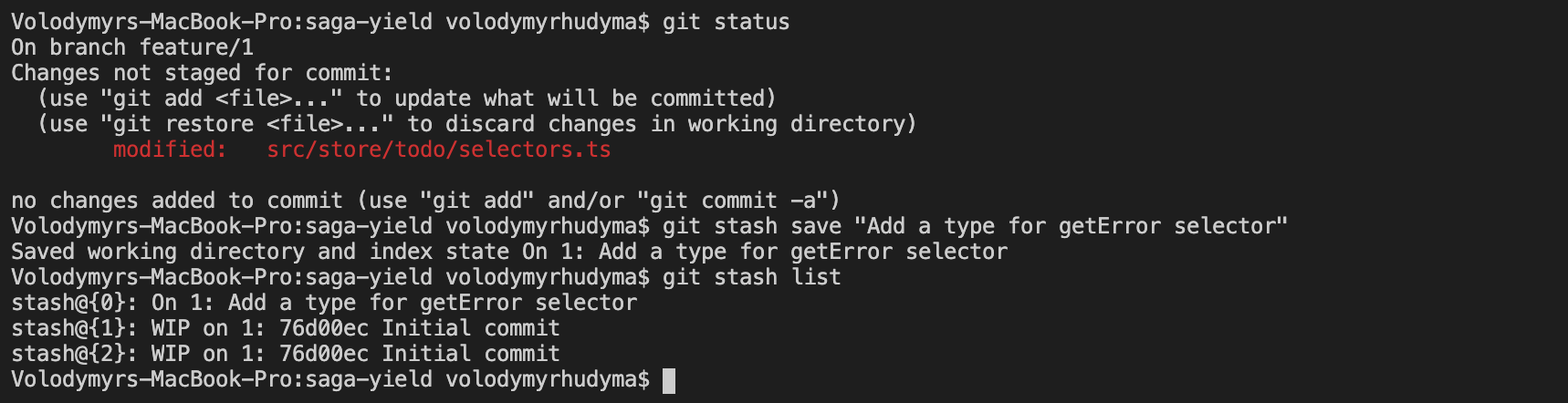

Describe Stash

Use the following command to add a description to the stash:

git stash save "<message>"

Let's make a small change in a file and stash it with a custom description:

Now it's much easier to guess what the given stash is about.

View Stash Changes

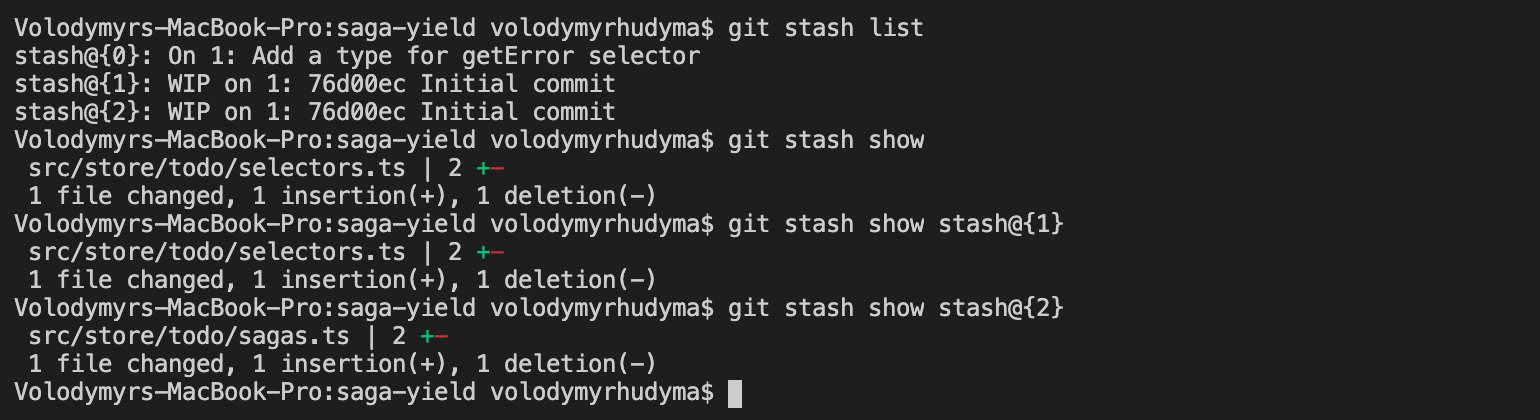

Sometimes it is necessary to look at the details of a particular stash to ensure that all changes are still valid and need to be applied.

This can be done with the following command:

git stash show (or git stash show stash@{<index>} if you want to view changes for a specific stash).

Let's quickly check what changes have been made to each stash from the list:

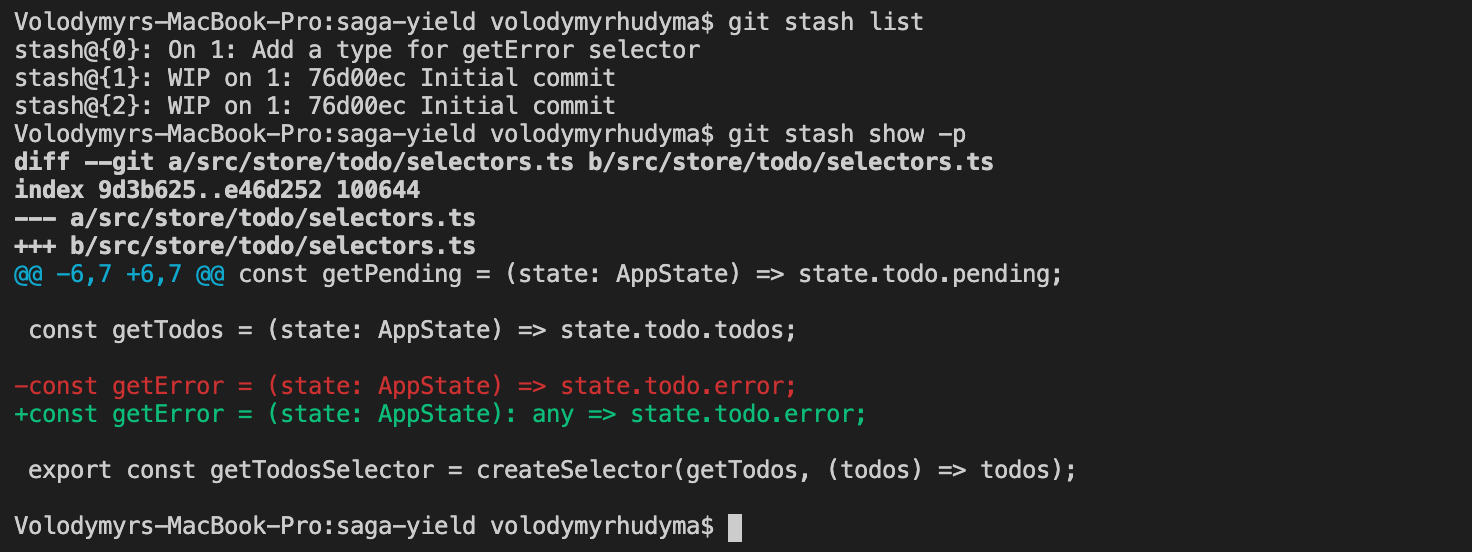

If we want to dig deeper and check which lines of code have been changed, we can add a -p or --patch flag:

git stash show -p / git stash show stash@{<index>} -p

Let's quickly check which lines of code were changed in the last stash:

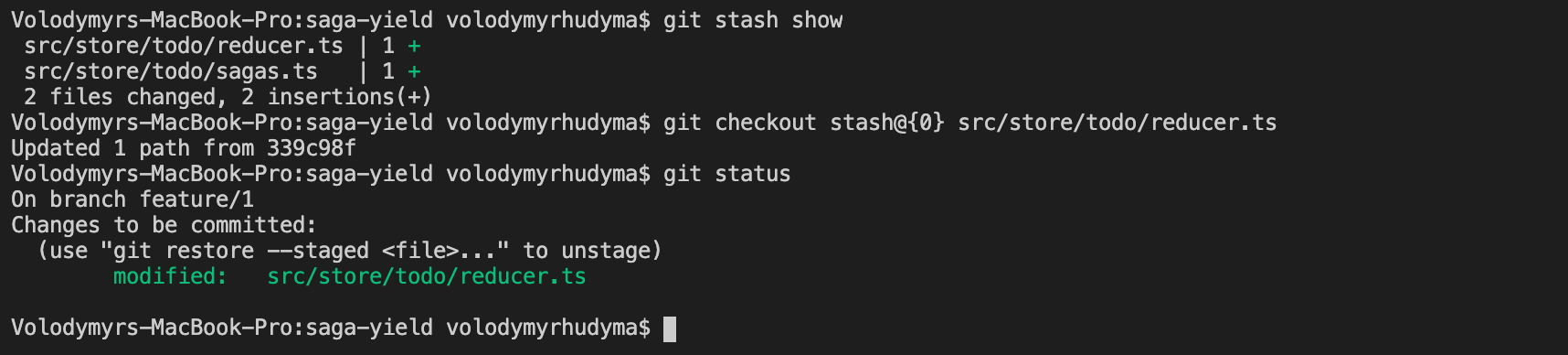

Apply A Single File From Stash

If your stash is old, some changes may no longer be valid, so you may want to apply only one or a few specific files from the given stash.

It is possible with the following command:

git checkout stash <file> (or git checkout stash@{<index>} <file> if you want to apply a single file from the given stash).

Let's see it in action:

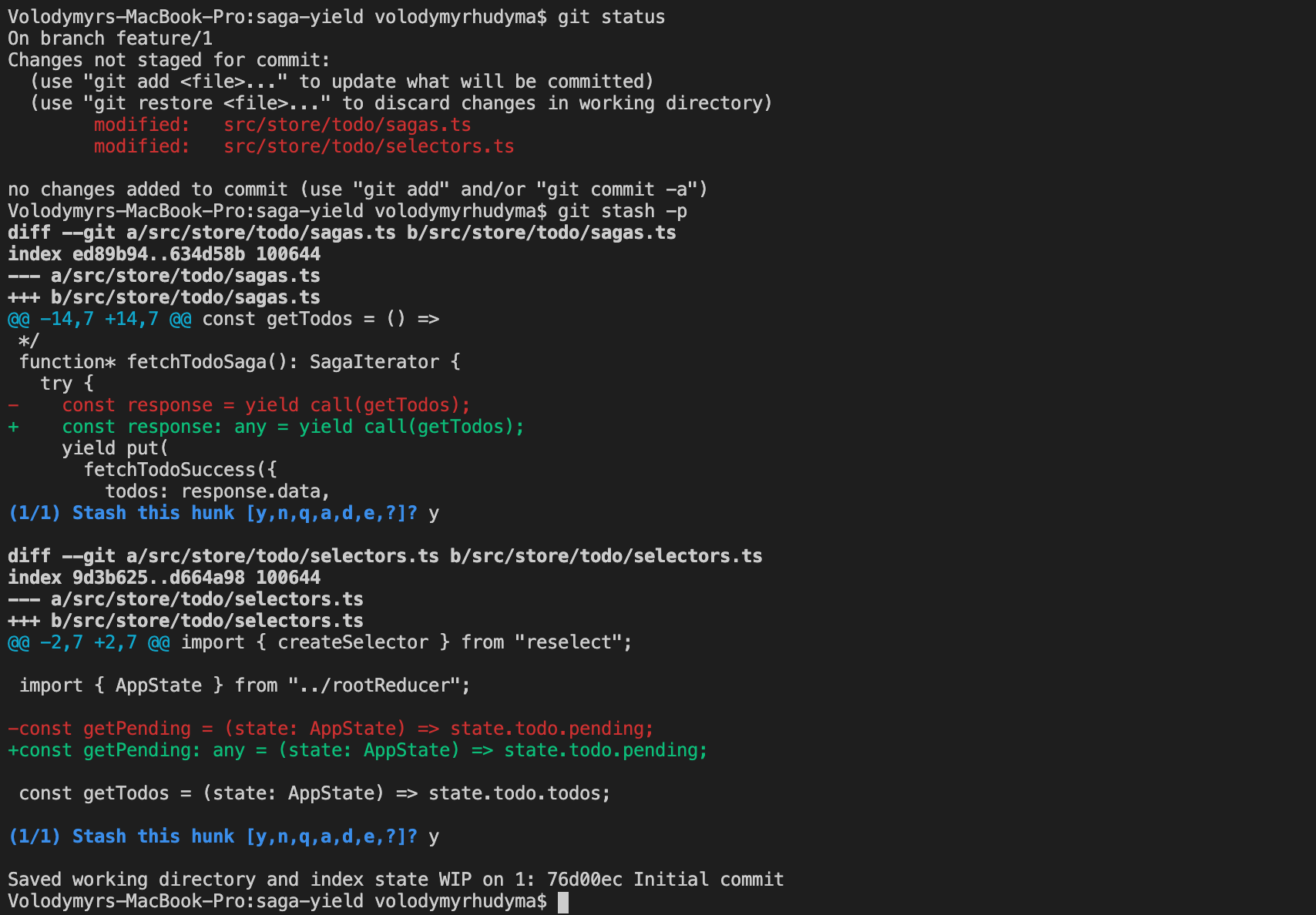

Create Partial Stash

In some cases, you may not want to stash all changes, but only the most important ones.

You can force Git to iterate through all changed files and ask you whether or not you want to stash a particular file by adding the -p (or --patch) flag to the git stash command:

git stash -p

Let's see an example:

In the above example, we have modified 2 files and for each file, Git asks us: Stash this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,e,?]?.

To cancel this operation, press Ctrl+C.

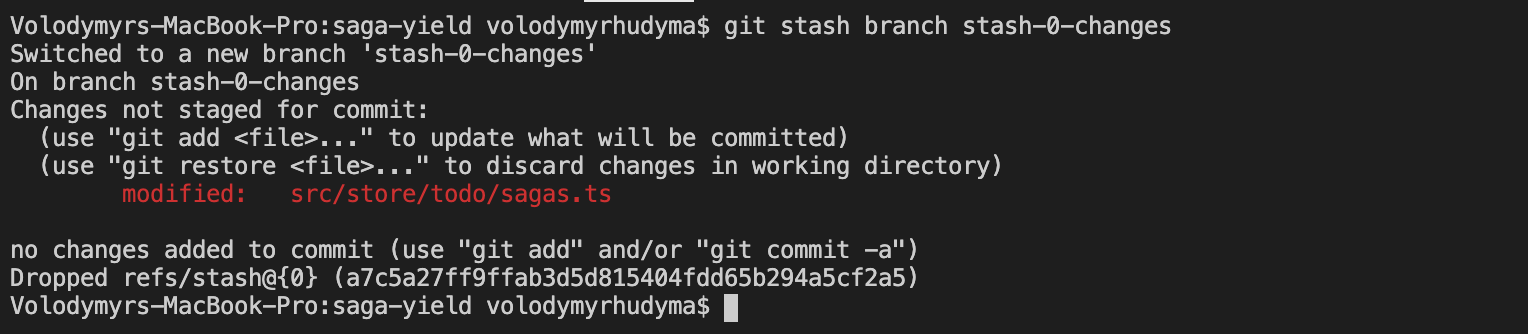

Create A Branch From Stash

It is possible to create a branch from the stash, which is very useful if the same files have been modified in the meantime and when trying to apply changes, you end up with a conflict.

The command to do this is the following:

git stash branch <name> (or git stash branch <name> stash@{<index>} if you want to create a branch from a specific stash):

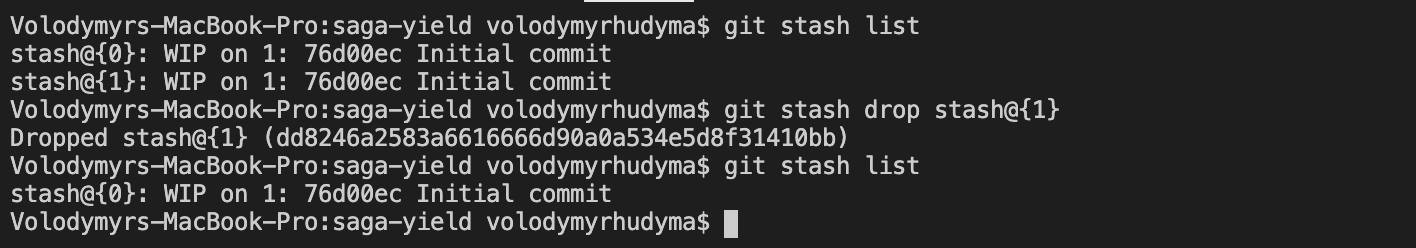

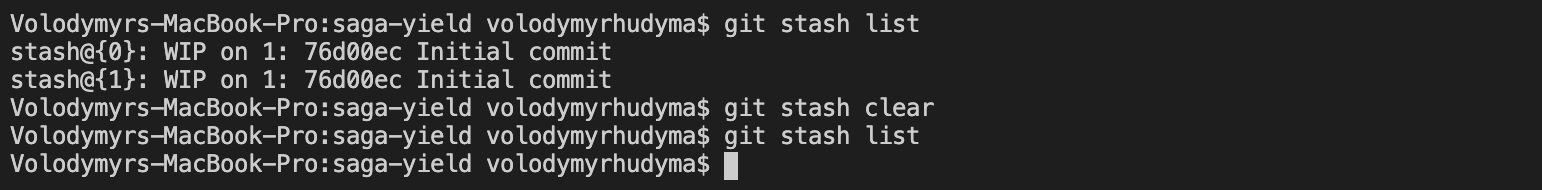

Delete Stash

A good practice is to keep your stash list clear by removing unnecessary items.

The command to remove a specific stash:

git stash drop (or git stash drop stash@{<index>} if you want to delete a specific stash):

If you want to remove all stashes from the list:

git stash clear

Example:

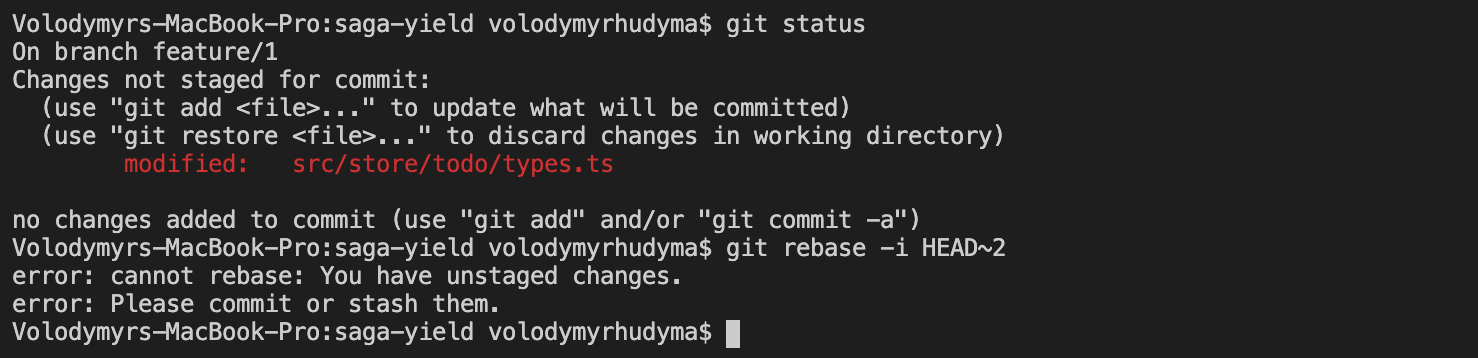

Advanced: Auto Stash

When you rebase, you must have a clean working directory, otherwise Git reports that something is wrong:

There are a few ways to fix this:

- Commit changes

- Discard changes

- Stash and re-apply changes manually

- Stash and re-apply changes automatically

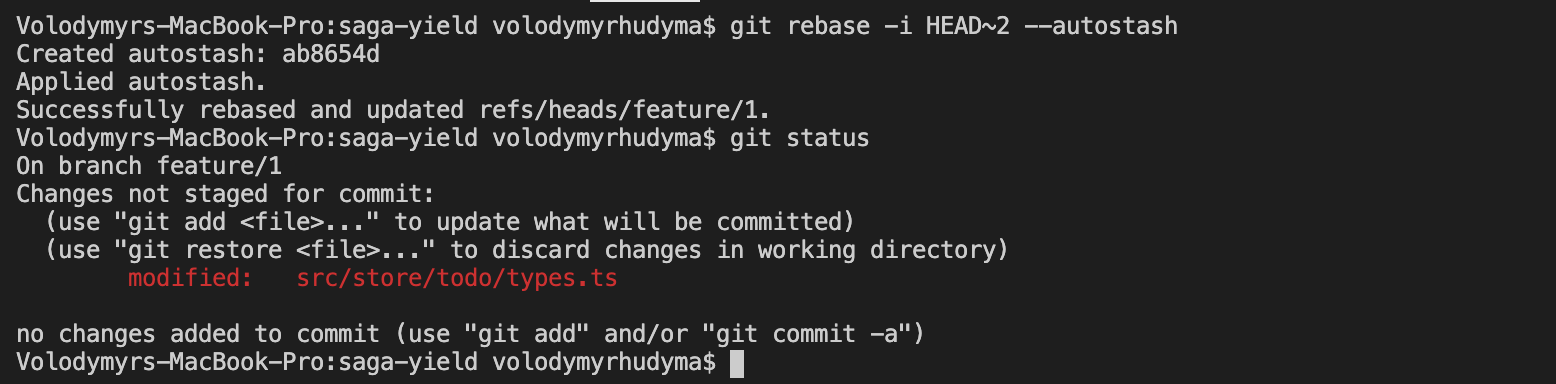

We will now focus on the last option, which is possible with the --autostash command.

With this command, the changes are automatically stashed before the rebase and re-applied after:

Cheat Sheet

- git stash - temporarily save the current state of a working directory and revert it, so you can start coding new features from scratch

- git stash -u - stash changes with untracked files

- git stash -a - stash changes with ignored files

- git stash apply / git stash apply stash@{1} - apply stashed changes from the last/given stash

- git stash pop / git stash pop stash@{1} - apply stashed changes from the last/given stash and remove it from the stash list

- git stash list - list stashed changes

- git stash save "Message" - stash changes with a custom description

- git stash show / git stash show stash@{1} - view files that were changed in a last/given stash

- git stash show -p / git stash show stash@{1} -p - view lines of code that were changed in a last/given stash

- git checkout stash path/to/file / git checkout stash@{1} path/to/file - apply a single file from the last/given stash

- git stash -p - force Git to iterate through all the changed files and ask you whether you want to stash a given file or no

- git stash branch

/ git stash branch - create a branch from the last/given stashstash@{1} - git stash drop / git stash drop stash@{1} - remove last/given stash

- git stash clear - remove all elements from the stash list

- git rebase -i HEAD~2 --autostash - automatically stash changes before rebase and re-apply them after

Summary

Congratulations, you made it to the end of this long story about the git stash command and ways to work with it.

This command works like a clipboard - it temporarily saves the current state of a working directory and undoes it, so you can start coding new features from scratch.

You can re-apply stashed changes at any time.

It's super useful when you need to quickly switch context and work on something else without losing unfinished work.

I hope you enjoyed reading this article and will use the git stash command in your daily work.